Early pioneers in object-oriented programming paved the path towards using Model View Controller (MVC) for graphical user interfaces as early as 1970 and web applications have continued using the pattern to separate business logic from display. This article attempts to clarify the use of Model View Controller within web applications — giving consideration to the fact that most developers will be building their application using an existing web framework.

Model View Controller

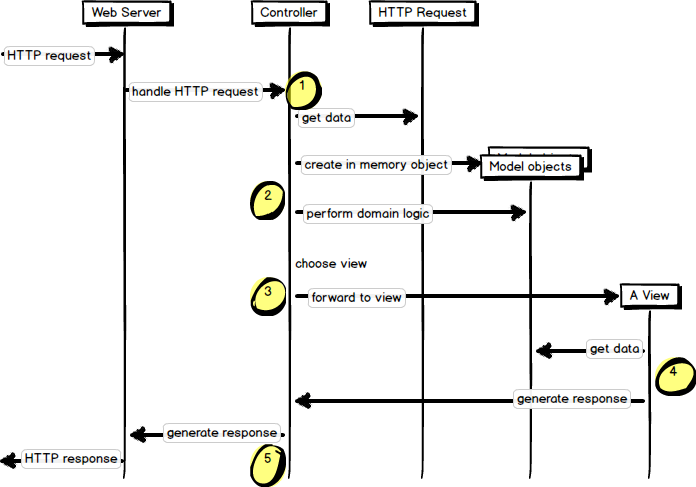

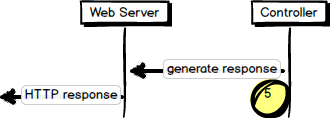

Let’s start our investigation of Model View Controller for web applications by examining a broad overview of how the Model, View and Controller work together to handle a single request to a web server. This diagram is adapted from the book Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture by Martin Fowler.

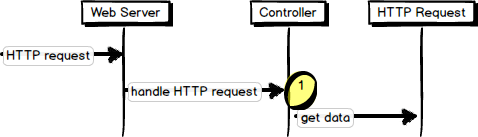

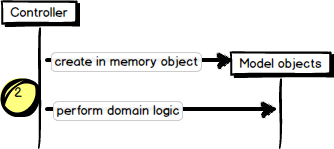

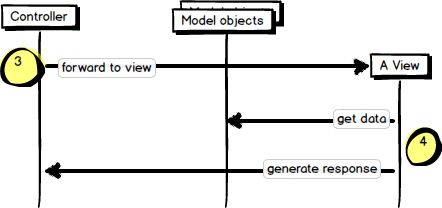

A request comes in to the application and is handled by an input controller (1). The controller parses any data that is on the request (e.g., query parameters, cookies, form data) and chooses the appropriate model objects and performs domain logic for this request (2). The controller chooses a view for displaying the result of the domain logic and data or model objects are passed into the view (3). The view uses this data to render the response (4). Finally, the response is returned to the user via the controller (5).

The most important reason for applying Model View Controller is to ensure that models are completely separated from the presentation. This makes it easier to modify the presentation independently of domain and business logic. Within this request flow the model objects are responsible for integrating with the persistent data source and potentially gathering information for display in the view.

Web Frameworks

Most web frameworks incorporate most of the functionality described by Model View Controller in their design. The Model View Controller and associated patterns were developed when web frameworks where in their infancy and largely outline the correct process to create a web framework from scratch. A common misconception for new web application developers learning Model View Controller is to implement MVC within their web framework. This unfortunately leads to a convoluted design with unnecessary layers of indirection during the processing of the web request.

My advice for new developers is to lean on your framework to implement Model View Controller and focus your attention on your business logic. As a concrete example, I will walk through a sample architecture for App Engine applications that uses webapp2, ndb, and jinja.

In this example file, App Engine acts as our web server implementing the WSGI specification. Once a request is received by the server it is forwarded to the webapp2 framework which handles routing to a Page Controller. So far, the WSGI application and webapp2 handle the creation of a controller to handle the request.

Model View Controller for App Engine

import webapp2

class HelloWorld(webapp2.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

self.response.out.write('Hello World')

ROUTES = [

webapp2.Route('/', handler=HelloWorld)

]

APPLICATION = webapp2.WSGIApplication(ROUTES)

We can start by implementing handling the request and customizing our response based on any incoming request data (1).

import webapp2

class HelloWorld(webapp2.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

name = self.request.params.get('name')

if name:

self.response.out.write('Hello %s' % name)

else:

self.response.out.write('Hello World')

ROUTES = [

webapp2.Route('/', handler=HelloWorld)

]

APPLICATION = webapp2.WSGIApplication(ROUTES)

Now let’s connect our application to a model (2).

The model in our diagram is connected to a data source and is responsible for converting from the data source to an in memory representation. ndb follows an Active Record pattern, providing a one-to-one mapping from the data source to memory, and a Table Module for . You could build up a rich Domain Model based on ndb. In my opinion the overhead of a Domain Model outweighs its benefits and you end up fighting against a pattern that is already available with ndb. For our simple application, our model is a user object that is created or loaded based on the query parameter passed in on the request.

import webapp2

from google.appengine.ext import ndb

class User(ndb.Model):

name = ndb.StringProperty()

class HelloWorld(webapp2.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

name = self.request.params.get('name')

if name:

user = ndb.Key('User', name).get()

if not user:

user = User(name=name, id=name)

user.put()

self.response.out.write('Hello %s' % user.name)

else:

self.response.out.write('Hello World')

ROUTES = [

webapp2.Route('/', handler=HelloWorld)

]

APPLICATION = webapp2.WSGIApplication(ROUTES)

We’ve leveraged ndb to handle mapping from our data source to an in memory representation and don’t need to define any special handling to interact with the data source. This is typical when working with a pre-existing framework and I would suggest caution when making any more complex data source transformations unless you are building your own framework. We also perform some simple domain logic in our controller. Since getting or creating a model is a common operation we may want to push this function to the model itself to provide reuse. The Active Record pattern that ndb implements lends itself to this structure.

import webapp2

from google.appengine.ext import ndb

class User(ndb.Model):

name = ndb.StringProperty()

@classmethod

def get_or_create(cls, name):

if not name:

return None

user = ndb.Key('User', name).get()

if not user:

user = User(name=name, id=name)

user.put()

return user

class HelloWorld(webapp2.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

name = self.request.params.get('name')

user = User.get_or_create(name)

if user:

self.response.out.write('Hello %s' % user.name)

else:

self.response.out.write('Hello World')

ROUTES = [

webapp2.Route('/', handler=HelloWorld)

]

APPLICATION = webapp2.WSGIApplication(ROUTES)

Now we’ve separated common functionality to the model and used the controller to coordinate the domain logic. As this application grows the controller can be leveraged to perform more complex domain logic on multiple models. If we find that we have two controllers performing similar logic we may want to move that particular functionality out into a shared script.

Let’s extend our example by rendering our page using a view.

We leverage Jinja to act as our view and provide the interpretation and rendering of our model following a Template View pattern. We’ve again kept our interpretation of Model View Controller simple by working within our web application framework rather than against it.

import os

import webapp2

import jinja2

from google.appengine.ext import ndb

JINJA_ENVIRONMENT = jinja2.Environment(

loader=jinja2.FileSystemLoader(os.path.dirname(__file__)),

extensions=['jinja2.ext.autoescape'])

class User(ndb.Model):

name = ndb.StringProperty()

@classmethod

def get_or_create(cls, name):

if not name:

return None

user = ndb.Key('User', name).get()

if not user:

user = User(name=name, id=name)

user.put()

return user

class HelloWorld(webapp2.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

name = self.request.params.get('name')

user = User.get_or_create(name)

name = user.name if user else 'World'

template = JINJA_ENVIRONMENT.get_template('index.html')

self.response.out.write(template.render(name=name))

ROUTES = [

webapp2.Route('/', handler=HelloWorld)

]

APPLICATION = webapp2.WSGIApplication(ROUTES)

Finally, webapp2 and the WSGI application and server handle returning our response to the user and completing the request-response cycle.

As our application becomes more complex, we may want to separate our code into separate modules for Model, View and Controller. I recommend including an additional module called Scripts that stores more complex interactions between models that are used in multiple controllers. However, since each request to our application is typically an independent transaction sharing logic between different requests should be rare. The final directory structure should look something like the following.

.

├── app.yaml

├── controller

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── index.py

├── main.py

├── model

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── user.py

├── scripts

│ └── __init__.py

└── view

├── __init__.py

└── index.html

The overarching theme of this article is to leverage our existing framework and libraries to implement the Model View Controller pattern for us. Leave your application simple and lean on your tools. Of course, design patterns are subjective and my opinion may not apply to your use case — take what works for you and leave the rest.

Full source code for this example is available on GitHub.